Team Based Learning

Introduction

Team Based Learning or TBL is a pedagogical format that brings together a number of evidence based practices to structure learning activities within the curriculum.

The process moves students beyond learning content, to using key concepts to solve problems in teams.

History

Team-based learning was developed by Larry Michaelsen and Michael Sweet in the USA. The method allows students to develop both conceptual and procedural knowledge in small groups, and can be scaled to large cohort teaching delivered by a single lecturer (or a lecturer supported by GTAs). Many lecturers find it a challenge to incorporate small group work and peer learning into large cohort teaching (which is often based in a lecture theatre environment), but Team Based Learning can help to facilitate this. Lots of detail about the development of Team Based Learning, examples, ideas and materials are available on the Team Based Learning website.

The Team Based Learning process

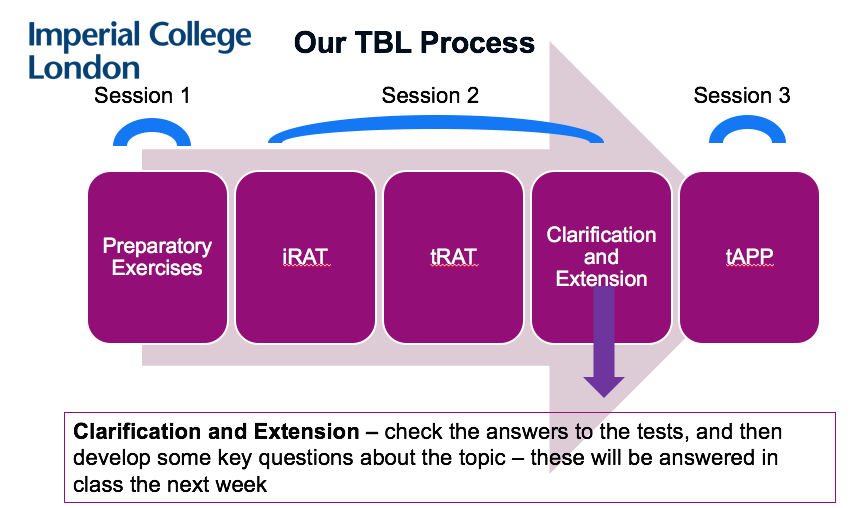

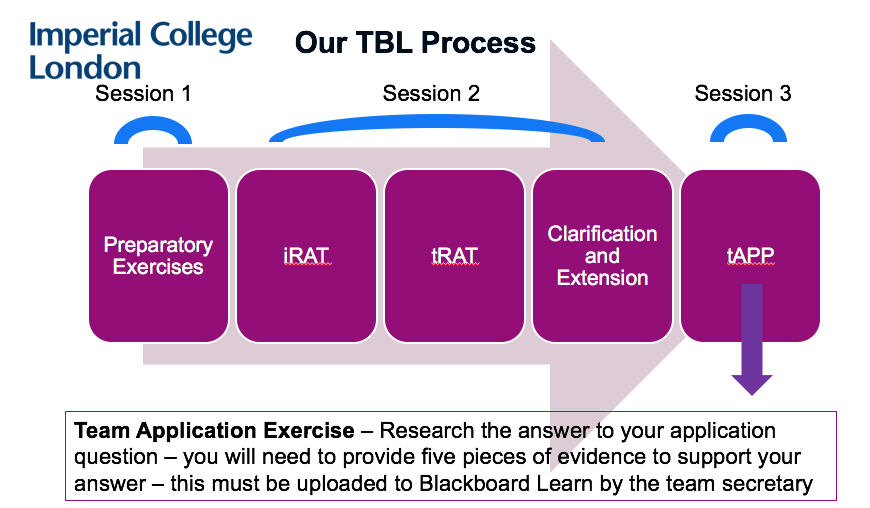

Students are introduced to a series of concepts over a number of ‘cycles’ of learning. Depending on the structure of your course, a cycle might be several sessions in one day, a number of sessions during a week, or, as in Global Challenges teaching, several weeks of sessions.

From the beginning of the course, students are assigned to teams. They work in these teams for the duration of the course, and although they complete some work individually, a lot of work is also completed as a team.

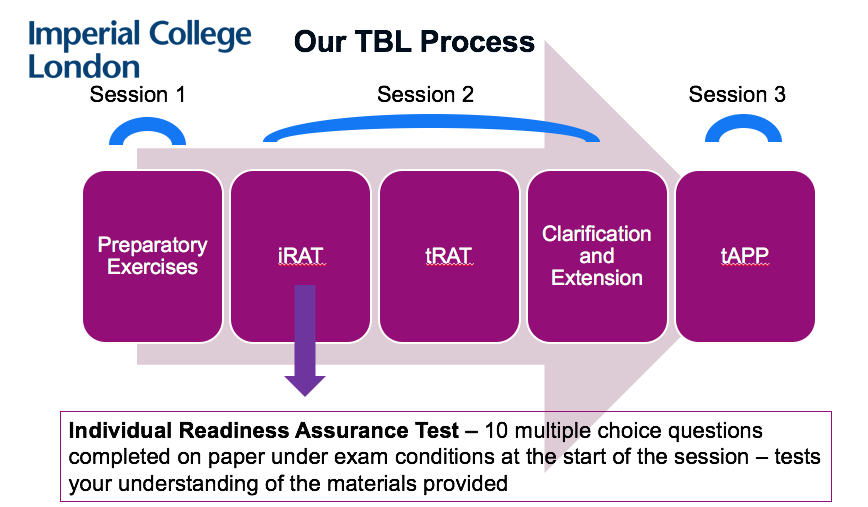

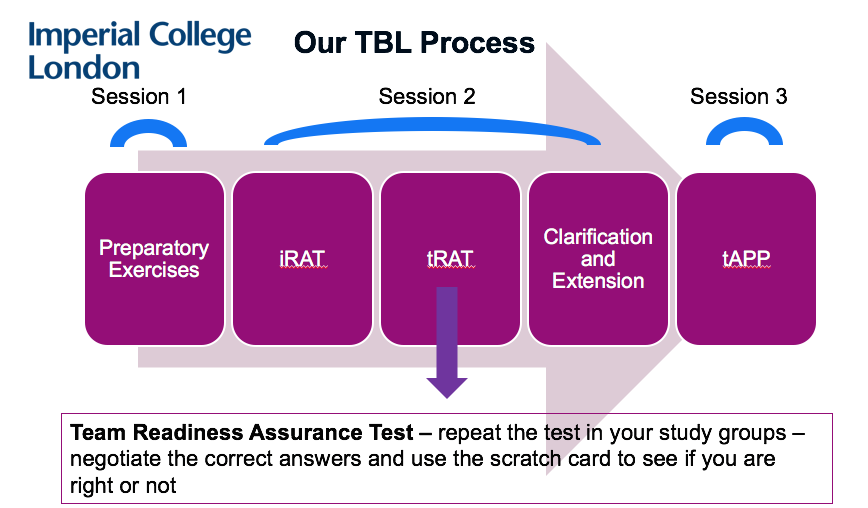

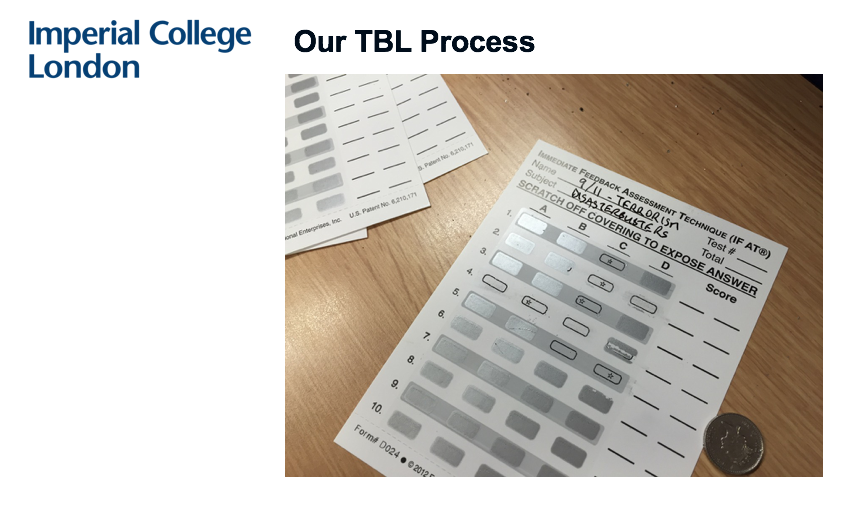

For each cycle, the students are given preparatory material. Reading time could be provided in a timetabled session (with or without supervision) or may be required as a pre-class activity. The students then sit an individual multiple choice question test called an iRAT (individual readiness assurance test). Following this, the students immediately sit the test again in their teams (tRAT or team readiness assurance test). This initial test reflects the student understanding of the preparatory material – highlighting any misunderstanding or lack of diligence in preparation. The students have a chance to challenge the lecturer if they feel that they have been marked incorrectly for what they consider to be a correct answer. Students might also challenge the nature of the questions, if they feel that something is unclear. Completing these two tests (or the same test twice, as is really the case) ensures that the students are ‘ready’ to move on to demonstrate an ‘application’ of the concept or material that they have learned. This is the tAPP or team application exercise. The application exercise provides a further opportunity for feedback before the students move on to the next cycle.

There are rather a lot of acronyms involved in delivering team based learning – however, we have found that the students quickly get to grips with these and using the labels (such as iRAT or tRAT) helps students to navigate the cycles and commit to the structure of TBL.

The Team Based Learning ‘Rules’

If you are following the Team Based Learning guidance to the letter, there are a number of rules that have been developed to ensure maximum efficacy of this pedagogical methodology. As I will explain, we break a number of these rules in our teaching. However, it is important to understand what the rules are designed to establish and protect, so that you can decide whether you will make educational gains or losses by breaking them, depending on your particular educational endeavour.

- Students are introduced to the process before the first educational cycle begins, and make a number of choices about how things will work – this ensures that students can fully engage with the process, know what is expected of them and can plan and monitor their own progress and learning

- Teams are assigned by the instructor – the teams should be as diverse as possible, and Michaelsen and Sweet propose a number of variables that should be used to achieve this

- Students prepare pre-set material before the class – according to TBL proper, the pre-set material is prepared in advance of the first session in each cycle

- The team test is the same as the individual test – this ensures that students understand how well they have prepared the material, and also learn how to negotiate answers within their team

- Students can submit written appeals after the test – students have the opportunity to challenge incorrect answers, or the wording of questions

- Appeals are clarified by the instructor – the instructor must make time for this in the class

- All teams complete the same application exercise – this allows you to monitor student progression through a set curriculum and ensures that the class cover the same ‘content’

There are further rules when it comes to the delivery of the tAPP (team application exercise). These are often known as the four ‘S’s.

- Significant – the groups should work on a question, problem or case demonstrating the concept’s usefulness

- Same – the groups should work on the same question

- Specific Choice – the students should be required to make a specific choice

- Simultaneous Report – the students should be required to report their answers at the same moment as the rest of the class – usually using a series of flash cards (labelled A-D)

A worked example – ‘Lessons From History’

This interdisciplinary course looks at historical global phenomena and disasters to see what lessons can be taken forward to help better prepare the world to tackle global challenges. It is an optional module undertaken by 3rd or 4th year undergraduates, and we have a mix of science, engineering and medical students. The course can be taken for degree credit (representing ~10% of the student year mark) or for extra credit (6ECTS) and consists of 20 weeks of two hour classes.

We look at a range of historical disasters including the Chernobyl disaster, the L.A. Riots, the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and the BSE Crisis. We also have some student choice cycles (where students choose the topic) that in the past have included topics such as Aral sea regression, the Challenger disaster, the Bhopal catastrophe, the Rwandan genocide, the Vietnam War, 9/11, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Great Chinese Famine, the Haiti Earthquake, the Eyjafjallajökull Eruption and many more.

Our goal is to answer the question of whether we can learn from history and each topic is explored from a range of perspectives (social, economic, political, ethical, technical, policy). We aim to develop empathic engagement with all the key individuals in each disaster (victims, perpetrators, community leaders, world leaders) and to look at critical decisions and choices in the context in which they were made.

Why did we choose to use TBL?

Using TBL allows us to give the students lots of freedom – they get to make choices about the structure and working of the course (for example, students can choose the exact contribution of various elements of assessment to their final mark from a range of pre-set options), the topics that they study (we have several cycles where students nominate and vote for topics of their choice) and the perspective from which they study the topic (student teams pitch for different perspectives on the chosen topics).

Including lots of student choice and allowing students to approach their work from different perspectives can sometimes introduce uncertainty in the learning process – both on the part of the learner and instructor. The rigid repeating structure makes our expectations very clear and helps to mitigate this.

TBL is a democratic process, so the students have a clear voice and make decisions about their learning (within the process). This is key to the Live, Love Learn approach and encourages students to take responsibility for their own learning, learning choices and assessment products.

The repeating structure allows us to practice procedural skills and microskills – especially useful for students with less confidence. We often have students electing to study this course who have very little confidence in writing. A strongly scaffolded approach to very small writing tasks with frequent feedback helps students to emerge at the end of the course having completed a long form essay and as confident writers, able to express their opinions and ideas and persuade others of their perspective.

The TBL format makes frequent feedback a learning tool that is integral to the learning process as a whole. This is motivating for the students and useful for monitoring impact and progress.

Our cycle structure

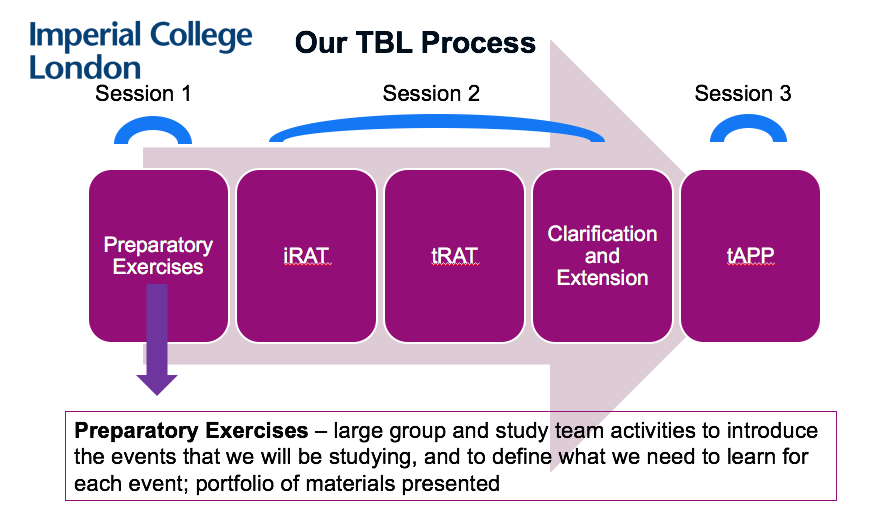

This slideshow takes you through our cycle structure. We have a three session structure, so for us, each cycle takes three weeks to complete. These are the same images we use to explain the process to the students and to remind them of the process during the first few cycles.

Our TBL process (and breaking those rules)

The ‘rules’ that we mentioned earlier are excellent for keeping you and your learners safe if you are following a traditional curriculum. That is to say, a curriculum with set content and procedural knowledge that must be developed in order to pass the course. Follow these rules, and although a TBL course takes some preparation and hard work to set up, you can feel reassured that good learning will take place. We break these rules because we have a very different, progressive type of curriculum – that’s not to say that you can’t break them with a traditional curriculum, but you need to appreciate what the rules are for, and make sure that you can anticipate the consequences of your amendment.

So what is so different about our curriculum? Firstly, we have a ‘process-based’ curriculum. This means that we are more concerned about what students can ‘do’ at the end of the course, than what they ‘know’. We have plenty of content in the course, but the content is there to facilitate practice at using the processes rather than as a list of items that must be learned. So our historical topics, rather than being ‘content’ to be learned, are tools for facilitating the practice of process. We do ensure that our students attain a basic knowledge of the historical events, but there is no exhaustive list of points to be learned. The processes that we are encouraging students to practice include

- assessing their own knowledge about a topic

- developing key questions about that topic to further their knowledge and understanding

- finding sources to address their knowledge gap

- assessing those sources for reliability, validity and quality (in terms of adding to their understanding)

- answering questions about their topic succinctly, referring to key evidence and persuading the reader of their conclusion

This means that we don’t require every student to learn the same thing as the next student. While we ensure a minimum level of core content, we encourage the students to tackle different perspectives and share this with their whole cohort by documenting this on a class wiki. Each student team therefore has a key area of depth of understanding, with access to a wide breadth of information. They document their research and analysis using annotated bibliographies and case summaries.

The core knowledge itself is also determined by the students. They must decide what is an appropriate level of understanding to have about a topic they can claim to have studied. As the students see what other teams have decided is critical to a core knowledge base, they self moderate over the course of the cycles, and in the end, each team is documenting the same level of material as ‘core’. In one sense it is not important what they decide to include as core knowledge, it is the negotiation, understanding and responsibility of making the decision that is key. This is a highly transferable skill, but is very hard to ‘teach’ when you have a ‘content’ based curriculum.

Back to the rules. And the rule breaking.

- We do our preparation together – we have a whole group preparatory exercise and then dedicated reading time in session 1. We use this time to develop an awareness of our existing knowledge as a group, and highlight key gaps in knowledge. We then use these to structure the allocation of perspectives to different teams. Each team then researches some core knowledge about the event, then develops questions relating to their particular perspective and looks for evidence to answer those questions. The students are given a set reading that is on a topic related to, but not directly about, the event in question. For example, for the LA Riots cycle, the students might be given a reading about police brutality.

- We don’t do written appeals – all our appeals must be made verbally in front of the whole class, and discussed and resolved with the whole class. This puts more responsibility on the student to ensure that their appeal is reasonable and worth pursuing than the indirect submission of a written appeal. It also allows the whole class to get involved in moderating the appeal, discussing it and contributing to the resolution of the appeal.

- Our application exercise is completely different – each team writes their own question relating to their own particular perspective. Each team member then documents and provides three pieces of evidence that pertain to the question in the annotated bibliography. The team then selects the five most pertinent pieces of evidence and writes a 250 word answer to the question together. This is completed on the wiki and is visible to all the other teams. Written feedback is given on all aspects of the task from the question, to the selection of evidence to the writing of the answer on the wiki. The feedback is also visible to all the student teams (the grade is private to the team). The detail of the feedback really helps the students to hone their writing skills quickly.

As the cycles progress, the cohort develops a detailed and comprehensive online resource. Their final assignment of the course is an essay of their own design. They must write their own essay question, explore the relevant issues, include their own thoughts and opinions and answer the question persuasively. The wiki becomes an incredible resource for this assignment as they can access all the fully annotated research of all the student teams from the whole course.

The essay in itself is also a little unusual in that it is completed in class time, using the essayathon. But that is a whole different topic.

References and further reading

Michaelsen, L., Sweet, M. and Parmelee, D. (2008) Team-Based Learning: Small Group Learning’s Next Big Step: New Directions for Teaching and Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

[…] based learning course and more details of the overall structure of the course can be found in the team based learning article. Broadly speaking, the students work in teams to learn about various disasters and phenomena in […]