As part of our new Teaching and Learning Strategy at Imperial College, the Education Office has launched a series of ‘Talking Teaching’ seminars:

The Talking Teaching series will showcase best practice approaches to teaching from around the College.

I was invited to present briefly at the second of these meetings, which have so far attracted a large, engaged audience from across College. There was also a second presentation from Dr Sophie Rutchsmann which described the introduction of a new series of sessions to help MSc students read scientific papers more strategically.

Inclusive and Participatory Learning Design

I presented on ‘inclusivity’ in learning design. Given the very active context of my teaching practice, it seemed sensible to combine this with ‘participatory learning’ as this is where there are some nice clear examples of how I try to enact ideas relating to inclusivity in the classroom.

I felt a little uncertain as to how to approach the broader topic of inclusivity as I wasn’t sure how my colleagues would view this concept. So I began by describing my own path to understanding and working with inclusivity in my learning design.

I wasn’t initially too aware of the idea of inclusivity when I began designing very active curricula, and when I first came across the concept I panicked a little. Active learning presents clear challenges to inclusivity – the more you require of students, the greater the number of potential barriers that might emerge to prevent the students from fulfilling the role you have designed for them. I wasn’t sure how to maintain an active classroom while still making sure not to exclude anyone. The list of factors that could potentially lead to exclusion seemed endless – disability, cultural background, language proficiency, previous educational background, gender, sexuality…

The key for me was beginning to understand that a very simple side-step in thinking would bring inclusivity and active learning together. Instead of worrying about excluding particular types of student, I should be designing to include everyone – designing each active and participatory learning element with a range of supportive and inclusive measures to facilitate students’ engagement whatever their starting point, perspective or perceived ability.

In the real-world classroom, our students don’t necessarily present as individuals with particular needs or vulnerability to exclusion. They may or may not disclose factors that make their learning experience challenging. They may or may not know what might make their learning experience easier or harder. Students are dynamic and complex individuals, and from place to place, minute to minute, experience to experience, they might find different factors present barriers to their engagement with learning.

As educators, we therefore need to rely on more than just not excluding particular student stereotypes. We need to worry about, and design for, including everybody.

It is also important to consider how and when inclusivity should be designed for. If you think about inclusivity as preventing exclusion of specific students, then this is a ‘known’ quantity. You can design this sitting in your office. However, if you think about inclusivity as including everybody, this is a rather more unknown quantity. And I don’t believe that you can really be inclusive in this sense, sitting alone in your office. You need to have a sense of who you are including, and this only comes in the classroom. So you need to design opportunities to be inclusive, rather than inclusion itself. It is also critical to appreciate that this type of design doesn’t have an infinite legacy. It works in one particular moment, on one particular day, with one particular group of students. It may well work differently in subsequent iterations, and this needs to be considered in the design.

In this seminar, I went on to describe three examples of how I attempt to create a culture of inclusivity in my learning design – learning contracts, continuous feedback and collaborative learning outcomes/assessment criteria.

Learning Contracts

As part of the Live, Love, Learn approach we create challenging learning experiences that often subvert the typical model of expert teacher and novice student. We empower students to explore and develop their own sense of expertise, conducting library and empirical research to develop their own understanding of real-world complexity.

We initially found that the lack of a recognisable ‘lecturer’ figure impacted the students’ understanding of their own engagement with the learning experience. Many students, despite demonstrating extensive learning and development during the course, would report that they had not been able to learn anything as there had been no ‘teaching’.

We decided that we needed to tackle this with an explicit discussion of the role of the student and the role of the teaching staff in our courses. We captured this in a contract of expectations – with a paper ‘contract’ that detailed the commitments and expectations of the student on one side, and those of the teaching staff on the other. We both (student and teacher) signed this contract at the start of the course. Later we developed this to ask students to define their own commitments and those they required of the teaching staff, and the contracts moved into the ownership of the students, with mediation and moderation from the teachers. This also allowed groups of students to incorporate their expectations of their team mates.

Not only do the contracts form a useful basis for commencing our learning together, but they provide a useful point of reference should any recourse be necessary. We can use the contracts as the basis of any discussion that is needed about commitment to learning, classroom or collaborative behaviour or the work that is required of the students. Students, too, can use the contracts as the basis of a conversation with teaching staff about any issue that is impacting their learning, engagement or satisfaction with the course. Having the ‘prop’ of the contract can often help students to begin what might seem like an intimidating or challenging conversation, leading to measures being taken to offer them further support or to resolve any issue that might have arisen.

The contracts have been recognised as good practice by our external examiner, and also by colleagues around College. Civil Engineering developed our use of the contracts to formalise the output of a series of workshops with their first year undergraduates about ‘Expectations, Responsibilities and Diversity’. Students worked in teams to create learning contracts which were then amalgamated into a grand master contract by the lecturer. This was then presented back to the student teams, who were invited to make any amendments they felt were critical and then to sign the contracts. Rather spectacularly, these were then pinned on the wall, creating a spectacle of engagement and agreement to inform the future approach of this cohort of students to their learning. The contracts included sections relating to wellbeing, learning, behaviours and attitudes and diversity.

Thanks to Dr Andrew Phillips and his team for sharing this with us.

Continuous Feedback

At a course level, we use dialogic feedback to scaffold the progress of students and to support inclusivity. We begin by asking students to reflect on their expectations of the course, the skills and experience that they bring to their learning and any potential barriers to their success. For example, in our first year class, we do this with a short learning pre-assessment.

We then document both informal feedback (given in the classroom verbally in response to good practice or advice given to improve working practice) and formal feedback (given in response to assessments). The growing feedback portfolio is returned to students after each assignment, and they also document a response to the feedback they have been given. In addition, they can indicate via a quick access checkbox if they require one-to-one follow up on any aspect of their feedback. Further to this, there are ‘always open’ portals on Blackboard Learn where students can flag particular difficulties or comments to the lecturer.

We also use continuous feedback within active learning tasks to ensure that students are able to participate as freely as possible, but also are able to benefit from the best practice generated by themselves or their colleagues.

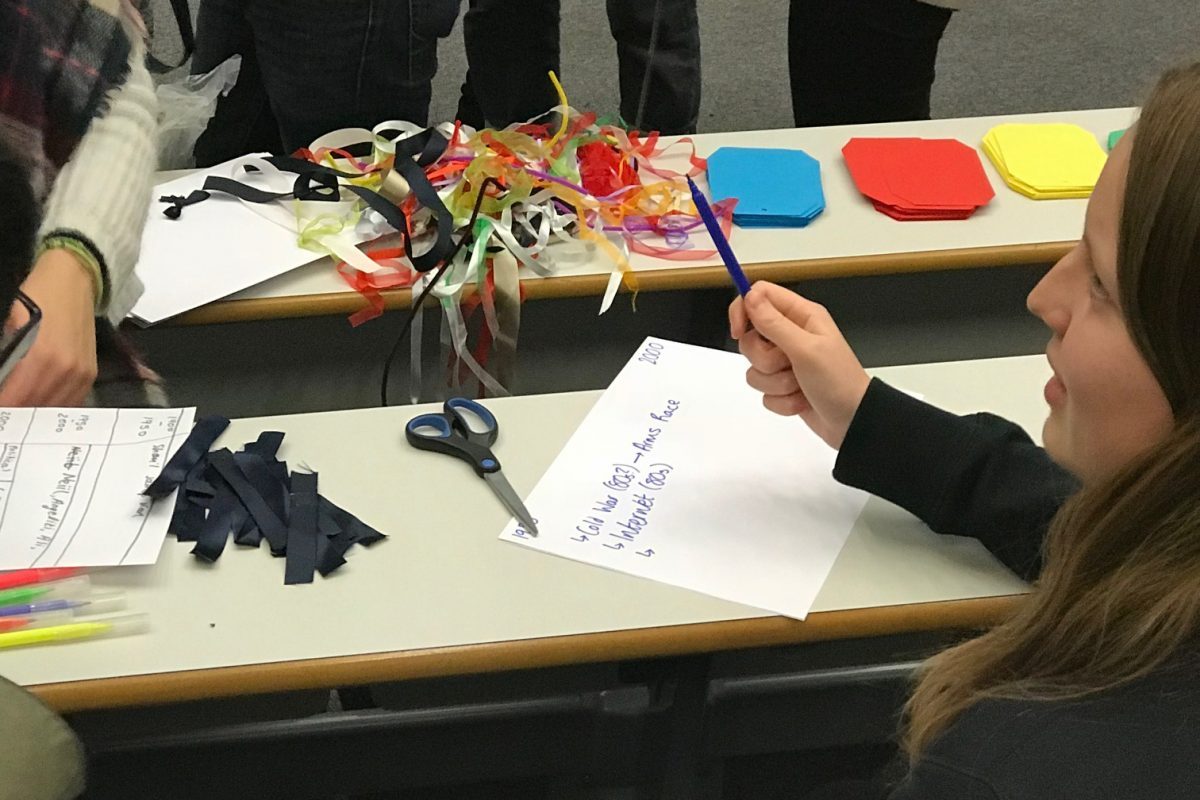

For example, we designed a large set-piece activity where our students would create a three dimensional timeline in a large raked lecture theatre. We divided our 80 students into two large teams and provided them with a brief, materials and a few ideas to get them started. We required the students to work effectively in teams of 40 – a tough task in itself. The students had to map extinctions, innovations and influencers that have shaped the known world over the last three generations, and to map future imagined examples over the next three generations. We provided rope, balls, canes, paper, multicoloured card, blu-tack, pipe cleaners, pens. Additionally, we suggested that one team use the visualiser and the other the projector to communicate key decisions within their teams (so that everyone across the full lecture theatre could share this information and act in a coherent way).

After every ten minutes, we interrupted the students and asked each team to describe what they had achieved so far, and what the next priority was. We also invited the other team to then offer suggestions or identify good practice. If there seemed to be sticking points, the teaching team offered some suggestions – both in terms of effective team working and on the content. For example, at one point, both student teams had got into a rut of just adding the births and deaths of important people and wars to their timelines. We reminded them of the brief, and then initiated a discussion about what other types of data point might be important to capture.

We also circulated in the interim periods to make sure that all the students were involved in some aspect of the task. By the end of the session, we were confident that 79 out of the 80 students had actively participate both in the generation and physical construction of their timeline. At the end of the session the teams peer-reviewed the other timeline, and then most stayed to help clear up (and to make new, non-timeline-related constructions out of some of the materials!).

Collaborative Learning Outcomes and Assessment Criteria

As educators, we use specific, limited vocabulary to describe learning. We all know about the desirable verbs for learning outcomes, and can match them to Bloom’s taxonomy. We use these same specific terms to create clarity and comparability across learning experiences, courses and indeed institutions. We use them for quality assurance. We use them to demonstrate what we are attempting to achieve.

However, students don’t necessarily all understand the same things from these terms. Some of them are particularly opaque to students. They come across the vocabulary frequently, so the terms are not unfamiliar. Some students understand them well. But some students do not. Some students can define and apply them, some can define them but without being able to apply them to their own learning. And some cannot actually define them at all.

In many of our classes, we publish learning outcomes for each session in our course outlines, but then co-create a maximum of three learning outcomes for learning activities with our students. We do this live, and it works well with small groups and big lecture theatre cohorts.

We begin by outlining the context and content of the learning to be accomplished. Then we ask the students what three things are most important for them to achieve in order to demonstrate that they have learned well from the session. One student will make a suggestion, we type it directly into Blackboard and then ask for alternatives and/or amendments. Over the course of five to ten minutes, we perfect some learning statements for the session together. They are usually not dissimilar in spirit to what we, as educators, had designed in advance. However, they often differ in vocabulary.

We also do this with assignment criteria. Although we publish our marking criteria to students in advance, we have found that students cannot always apply this effectively to shape their approach to the assignment.

For example, for an oral presentation session where each student team will present their collaborative work in a series of one minute presentations given by each team member, we asked the students to define some marking criteria. We asked the question – ‘how will we know if you have given a good presentation – what will we be looking for?’.

The students came up with the following list that we documented live on Blackboard and then used to peer and tutor mark the presentations.

The resulting criteria included one element that I had not anticipated would be important and that I would not have included in the marking criteria. The students were adamant that they should attribute and describe the main source for the information that they would be presenting. I would not normally have considered this critical in an oral presentation. However, upon reflection, we had spent a considerable amount of time encouraging students to not only include their sources as references, but also to comment on them in terms of whether or not they were useful, reliable, or methodologically sound. This was an important element of the work they would be presenting, so it made sense that they would include this. I’m really glad that the students suggested this, and I think that it enriched their presentations and improved the coherence between different elements of the course.

There is always the risk that when you include suggestions from students that they may want to include something that is not appropriate. In this case, it is up to the lecturer to explain why the suggestion would not work or would not be helpful. Students may also neglect elements that are very important, in which case it falls to the lecturer to try to elicit these additional ideas from the students. For example, I find that students almost never think that their ‘audience behaviour’ is important during presentations. I always allocated students specific tasks while they are listening to other students’ presentations, and rotate these tasks after each presentation so that the listening experience is varied. For example, students might be asked to provide feedback on a specific element of the presentation, or to ask a question at the end. But students don’t tend to anticipate this, and I nearly always need to prompt this when we are defining the mark scheme. A question to the students like ‘And what will you be doing while you are not presenting?’ usually begins a discussion about not using phones, encouraging and supporting the presenter and thinking of good questions to ask. The students usually then define an additional criterion around their audience behaviour.

So including the students in these design elements of the learning experience is not an empty-minded handing over of control to the students, it is an open-minded inclusion of their perspective, ideas and language.

Feedback from the Seminar

I was really pleased to have some questions after the presentation. The first was around evaluation of these measures. We briefly discussed continuous evaluation of inclusivity during the progress of the courses, and also more formal evaluation of particular elements of learning design. I will be giving a further seminar on this in a couple of weeks’ time in the Centre for Languages, Culture and Communication.

There were also some questions relating to using technology to enhance inclusivity and participation, and I described some of my experiences of using Mentimeter. I haven’t used it much this year following some very negative experiences with it the previous year. However, I will revisit the use of Mentimeter in the future.

There was also a nice write up on the Learning and Teaching Strategy blog, contributed by Dr Clemens Brechtelsbauer, Director of Undergraduate Studies and Principal Teaching Fellow in Chemical Engineering.