Working online brings plenty of obstacles to active learning, communication and engagement – but can they be overcome?

So as we’ve mentioned, we asked our students what they thought were the advantages and disadvantages to learning online – using our Check In question.

In this post, we are going to consider the disadvantages as reported by the students alongside the actions we took to try to overcome some of these difficulties. When the students completed this particular Check In, I wrote individually to each student to thank them for their thoughts and ask them if they had any ideas about how we could enhance our online experience – specifically targeting these particular disadvantages – and together we figured out a few good solutions.

Time zones, technology and internet access

Harder to check in on each other due to time difference

We consciously made a decision to allow our students to experience the difficulties of working in teams with students in different time zones, with different access to technology and different levels of connectivity.

We fully appreciated that this would cause considerable anxiety and hardship for students, but we hoped that this could be a useful difficulty, that we could fully support to allow students to develop strategies for overcoming the inherent difficulties of global collaboration and build online resilience.

We were very open with the students at the beginning of our modules, explaining why we had made this choice. And we found that students did indeed strategise and come up with excellent working practices to help overcome these difficulties. And as we saw these strategies emerging, we piled in with positive feedback and shared these great practices with all our students.

For example, in some teams, we found that students were writing summaries of all discussion and decision making and posting it in their team chat to help absent students keep up and join in – and they would leave questions and actions for the absent students. Those students then reported that they were able to engage easily with their team and felt included. Having the specific questions to respond to helped these students feel invited to participate and helped them direct their collaborative efforts in a direction that was then appreciated by the whole team. In some cases it was many weeks before there was an opportunity for the whole team to get together in the same video call – and this was a really joyous and exciting meeting, as they had already been working together so well.

Students were adept at integrating different technologies, and finding the most accessible baseline technology for their main work – with those able to use other technology only using it for presentation purposes or private additions to team work. We gave the students the freedom to use whatever technology they wanted – including abandoning our Zoom rooms to work in Teams if they preferred. As long as they left a joining link in their team chat so that we could find them if necessary. And this echoed our normal practice of allowing teams to work outside of the classroom and even class time if needed – as long as they let us know what they are doing.

We still have some students with poor connectivity, and we work around this as best as we can. Students can optimise their use of available bandwidth by only using their camera sparingly – to say hello for example, and by using chat or WhatsApp alongside the video meetings.

Forming Teams and Getting Going

Harder to break the ice to work effectively as a team

In the classroom, forming teams would be an integral part of ice breaking and getting to know each other. But in the online world, we had to allocate teams – which made for rather a blunted start to our team working.

We would normally complete all team icebreaking and acclimation activities within the first session – but in this more challenging environment, we split these activities over the first three sessions, integrating them with the first three class activities. This meant that there was still a focus on getting to know each other built into the class activities – to acknowledge that this ‘work’ was ongoing and to remind students that this was necessary ‘work’.

For example, with our first year students, we asked them to create Team Diversity Maps in their first week – exploring all the aspects of diversity and commonality within their team – in terms of experience, expertise and interests. The students had to find the best way to share this information (in the form of some sort of map) – presenting as much detail as possible.

The in the second week, we asked students to consider how the diversity present in their team could act as a superpower – making them resilient and capable, creative and effective – but also how this same diversity could creep up on them as a super-villain, tearing them apart, creating difficulties in communication, ideology and collaboration. The students had to present a strategy to show how they would harness their super power and keep the super villain in check, as well as creating a ‘Change Maker’ kit that would embody their values as a team in understanding and tackling global issues. Each team member had to suggest an object that would be accessible to all team members to represent each value. The students then had to assemble their kit and use it in all future tasks.

Finally, in the third week, we moved even further – both to get to know our team members more, but also to find out about the hundreds of other students in the class. We completed a task to post photos of our local environment (either at home or on campus, or on recent travels) – reflecting on the presence of global issues in every space that we occupy. These photos were posted on an interactive mega Google Map, which created an awesome resource and overview of our geographical locations, experiences and environment.

Accessibility and Ease of Working

It all takes more time

We actually anticipated that working online together would be ‘slower’. There’s the time taken to get everyone logged into a Zoom, all those pauses while people are muting and unmuting themselves add up, and it is just harder to make the same degree of progress when you’re not face to face. In particular, we include some quite complex activities in our sessions that are punctuated by lots of interruptions and developments mid-activity, and these would be very difficult to implement online.

So we had already ‘chunked’ lots of our activities into smaller, more achievable tasks – often running smaller segments of multiple activities in parallel so that students could progress through tasks in a simpler fashion, but cumulatively gain the same experiences and skills.

However, some students still reported that, for example, small group discussions and sharing research and ideas took longer over video call, than when you can just stick a bunch of paper in the middle of the table and everyone can browse it together.

And some students were reporting meeting multiple times between sessions to complete discussions.

As teachers we’ve been able to intervene a little here, and suggest some more efficient methods of team discussion and collaboration – highlighting what needs to be done in shared ‘online’ time, and what can be done in preparation or review individually. In this way, classtime and group study time can be more productive and efficient.

We’re still working on this, but we are developing a team efficiency tool to scaffold some different models of group working, to help with balancing and mixing collaborative and private study, online and offline work.

Technical problems

As anticipated, some students have experienced quite severe technical and connectivity problems. While we would like all our students to have the same experience and opportunities to participate, we have tried to be as flexible as possible and have built in variations and alternatives to our learning design to try to accommodate everyone with every type of accessibility profile.

While we do require all students to be able to access Basecamp, we are very flexible about the Zoom/Teams video requirement, about students joining classes solely using chat functions – or even those interacting using completely novel tech solutions.

Apart from approximately five students out of several hundred having some teething issues with Basecamp, all other students – irrespective of their quality of internet connection have managed to use Basecamp successfully. However, not all students have been able to access Blackboard this term (we only used this very sparingly for some quizzes), and many have issues with Teams.

Some students experience Zoom as ‘tetchy’ – especially if they have intermittent or poor quality internet connection. However, this hasn’t been a huge issue – and many students have found that they get a better connection at different times of the day, and we’ve been able to have great Zoom catch ups during our optional Mix and Match hours.

We have also had to be mindful that not everyone is joining class on a laptop, and some technologies (like Zoom) have different functionality on a phone or tablet, and if joined from a web browser compared to a downloaded application. However, we have been able to resolve all these issues, and generally the host can implement functions on the behalf of students that cannot access them directly.

Communication and Body Language

Harder to communicate

Discussing problems in larger groups has been rather difficult

Taking non-verbal queues over during a conversation is harder virtually

The use of expressions and gestures are not easily communicated

It’s quite difficult to gauge people’s feelings and emotions from behind a screen. Sometimes it can be difficult to understand what they are saying or what they try to mean because we have a lack of visuals–can’t really see hand movement or body language which are essential aids to our understanding.

It can fall short. This occurs when you are trying to gain intuition on how people react to your ideas

We initially thought that active discussion would be very difficult on Zoom – but although it is not quite as easy to manage as in an in-person setting in the classroom, we have had some fantastic discussions.

Leaving enough time for people to respond and join in means that there are some pretty awkward pauses – but we have found that by acknowledging that at the start of the discussion, and by intermittently thanking everyone for being patient and generous, these pauses have become quite tolerable. And once you get into a bit of a rhythm, it is not so bad. We began using the ‘digital hand up’ system, but then found that students were actually quite good at getting our attention by either just turning their microphone on and coughing (to bump them to the top of our screen) or by waving madly. We can then invite them by name to share their ideas – which is doubly nice as we use each other’s names and pace the contributions.

Another useful tactic is to use the student teams – so our student teams in some modules have designed their Zoom backgrounds so that they are identifiable as belonging to their team. Both for other students and the teacher this means that we can, for example, say ‘Team Apple, do you have any thoughts on what David from Team Grape just said – and that means we can focus our attention on the select few students (out of the hundreds) that have been invited to speak.

We’ve also found that by providing alternative means of participating, more students join in – so for example, they can post comments in the class chat, or share photos and examples of what we are discussing. Sometimes it is possible to bring this into the live discussion, and sometimes we use this to continue the discussion after the class. We always acknowledge every contribution and follow up with a private Ping message of thanks for the contribution.

The body language issue is quite pervasive, but we did manage to gain quite a bit of ground with this in our first year module.

Once we saw the feedback about the difficulties understanding and being understood because of the lack of body language, we decided to tackle this quite explicitly while the students were preparing for mini-presentations.

We have each student speak excitedly about the most interesting thing they have come across in the module for one minute. They don’t plan their minute, they just introduce themselves and their topic and start speaking, only stopping when they hear the buzzer (and the rapturous applause).

We always speak a lot about how to ‘speak’ successfully. For us it is about confidence rather than language ability or the complexity of your ideas – we’re trying to be engaging and express our own passion. So what if you don’t feel confident?

We always explain that it is not the role of the presenter to ‘feel’ confident – rather it is the responsibility of the audience to make the presenter feel valued and interesting – and therefore confident. And the audience do this with their body language – subtle nods as they listen, not looking away if the presenter looks at them – holding eye contact for a few seconds. Smiling. Willing the presenter on. And of course, rewarding the presenter with deafening applause when they are finished.

And we always find students engage with this really well, and have amazing presentation sessions.

So this year, we merged this with a wider discussion about body language online. About how important it is to position the camera well, look up when you’re listening, smile, nod. And not smile and nod inwardly, but smile and nod outwardly. And bigger than normal. To call each other by name when having discussions so that it is clear who you are talking to and who you are inviting to respond to you. And in teams, developing your own shorthand to manage discussions – will someone lead and direct people to speak in turn, or will you use the digital hand, or the physical wave? To summon up emotion and try to show it in your face and voice, but if that is hard, to narrate it – whether the emotion explains your mood or your response to what someone else is doing or saying (I’m so happy to see you today, I really love your idea, I felt so excited when you explained it; I’m sorry I’m feeling a little down today – but I really like your idea, I think it will work well).

And after this session, we asked students to reflect on their experiences together. And we got the most amazing outpouring of mutual admiration, pride, gratitude and comfort that the students felt they had experienced in their session following this discussion. Basically they felt that they were surrounded by amazing and awesome individuals, and in turn had been valued and made aware of their own amazingness and awesomeness.

One of the best moments of the term.

Becoming a digital-only lonely inhabitant of the classroom

Much harder to share your work, and work together on paper

Sitting in front of computer feels less sense of participation

A sense of feeling left behind since you don’t physically see your classmates

Does not fulfil the required social networking

You lose that social interaction you can have with in person lectures as well as talking to course mates about work or whatever

Many students found that they were missing being active in classes, using materials and objects and being able to collaborate practically. And they missed all the informal communication opportunities to chat to other students walking to class, sitting in class, while working and as they pack up and leave the class.

We tried our best to overcome these difficulties, without requiring students to purchase materials or access items that might not be universally available and without awkwardly engineering chatting (well we engineered it, but hopefully not awkwardly).

So early on, we asked the students to make their own Change Maker kits (as described above), which we encouraged them to use them to complete future tasks. As each physical item in their kit was attached to a skill or attribute, this challenged students to mindfully use those strengths in doing the subsequent activities.

And we also found some opportunities for students to physically create material-based contributions to activities.

We would usually have a session where our first year students are thinking about the future. They come up with a premise about the future, and map different consequences of that premise – so for example, if the cure was found for cancer, there would be an increasing and increasingly aged population.

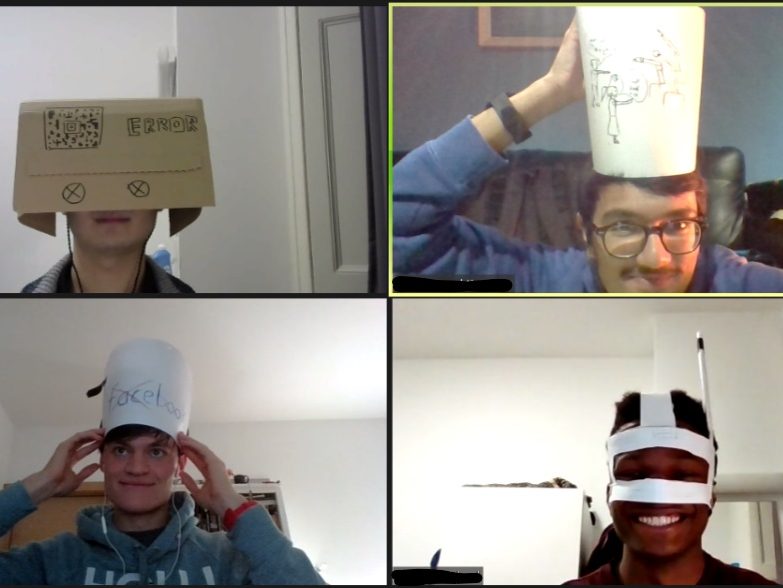

Each student team would pick one premise and then each individual in the team would pick one consequence and then the students would make hats to represent their consequence. At the end of the session, teams would present their hats and there would be a final integrative activity – some years the students where their hats and get plotted into a giant graph of the future, while some years we would form a conga chain, and students would be inserted into the conga line according to the likelihood of their future coming true.

But I would always provide all the materials. And students would be free to work in groups, crafting their hats together, sharing ribbon and pipe cleaners freely.

And the one thing that we hadn’t facilitated much in the module to this point was one to one conversation.

So for this activity, we asked students to collect their recycling over the period of a week so that they had some materials to work with. We hoped that this would make the activity equitable and accessible for all.

Then we opened the class zoom about half an hour early and created the most zoom rooms we’ve ever seen in one zoom. And as the students arrived, we asked them if they wanted to work with someone in particular, or fancied a ‘lucky dip’. And within the first twenty minutes or so, we had over a hundred students working in pairs and threes (according to their preference) on making hats.

We told them that the activity was 10% thinking about the future (and therefore ‘learning’, 20% imagineering (skill based learning), and 70% social interaction (wellbeing, social and peer learning). We asked the students to talk about whatever they felt they were missing out on – Netflix, gossip, sports, fashion – whatever – as long as they also did the 10% thinking and the 20% imagineering. And we gave them an hour.

When the students came back to the class zoom, they were excited and jubilant and refreshed. They all wanted to share their hats – we had asked them to take a screen shot of their zoom room with them all wearing their hats, and bring the photo back to the main zoom.

And then in a rather chaotic free-for-all, they ‘plotted’ their photos of their futures hats onto a Miro graph.

It was pure chaos, and some teams presented and some didn’t – but for those who couldn’t cut through the chaos, we had a chat open for posting photos and descriptions of futures. So one way or another, everyone shared their future. And no one seemed to mind the messiness of what was happening – they just migrated to the quieter chat, or persevered with getting their image plotted.

I didn’t know if all the pairs and threes would hit it off, maybe some people would end up in a room with someone they didn’t get on with, and maybe there would be some complaints or people who didn’t like it. But we never heard any negatives from this session – just many many positives.

So we will definitely be looking to create online-offline-mixed-mode activities that can be completed in pairs over a cup of tea in all our modules.

It is hard to concentrate while studying in the comfort of your room

With students working on independent projects, that don’t need frequent collaborative opportunities, we have found that students value a ‘quiet’ zoom. They like to log into the video call, cameras on, and work quietly in companionship with each other. And if they fancy a chat, they take themselves into a Zoom room (set up ready and waiting for them), before re-joining the meditative quiet working space.

The issue of the tutor not being able to see your work makes it harder

Communication with lecturer and professor are not that convenient

We learned quite early in the term that it is really important to always create several ‘spare’ zoom rooms – even if rooms are not being used in a session. This means that you can go and have a quiet and private one-to-one chat with a student or group of students – much like if they had approached you at the front of the room.

We also make sure that the teacher is logged on for fifteen minutes prior to class and after class, with their zoom class running and open so that students can grab a quick few minutes if they need. And we have our three hours of drop in sessions in the mornings.

We also take great care to learn the students’ names (much easier when they are written on the Zoom screen) and remember our prior interactions – even in our very big classes of over 200 students. In fact we kept some crib notes for that class.

We have also taken a lot of care to respond and react to all student work, comments and chat on Basecamp. We know that students might feel invisible at the start, but we actually see a lot more of them than they realise and we have to be very explicit in making that apparent.

Not as strong a feeling of urgency with deadlines and watching lectures since they are not as set and we’ve only seen the staff virtually

We realised after our first assignment in each module that students were experiencing deadlines differently than they might have in a face to face class. We had a record number of non-submissions.

Since then we have moved all deadlines into class time, so that we approach the deadlines along side the students, and can inject the necessary urgency, energy and excitement into the countdown to submission – while being on hand to provide feedback, support and last minute strategising for students that are really up against it.

This has worked really well, and we’ve had 100% submissions since then.

And finally a hidden bonus of these difficulties

You lose that social interaction you can have with in person lectures as well as talking to course mates about work or whatever.

But this helps massively with mental health as this is an effect usually kept behind closed doors.

But here, because we’re paying attention to these things, it is more out in the open.

The care and attention, and explicit discussion of the difficulties of working online, and of the consequences of the pandemic and various varieties of lockdown and social restriction being experienced by students, has surfaced a new, shared and open awareness of mental health and wellbeing that has been beneficial.

For us, in our classes, wellbeing has been central. We’ve tried to adapt and bend every activity, every learning outcome and assessment that needs to be completed to also accomplish positive wellbeing impacts – whether that is physical, social or emotional.

And hopefully this is a part of that beneficial opening of the doors on issues that students previously felt less comfortable addressing, discussing or disclosing.

Interested to know more?

Find out more about Change Makers online with the following posts:

The Virtual Classroom – come on a tour of our virtual classroom

Inclusivity and Hospitality – how are we welcoming students to our virtual classroom and addressing inclusivity online

The Rolling 24 Hour Class – how have we adapted the concept of the class to engage students in every time zone

The Check In – using a weekly reflective question to enhance learning, monitor attendance and engagement and target welfare checking

Change Makers (More Than A) Handbook – creating a handbook that is accessible and encourages students to read more about their learning

Does Working Online Have Any Advantages? – what have students been telling us about the benefits of working online

3 Replies to “Breaking down barriers to engagement online”